By John Banks, CCWP secretary-treasurer

Photo Detective: Inside An 1864 Burial Photo

Photo Detective: Inside An 1864 Burial Photo

The scene above, photographed by Mathew Brady’s operators in Fredericksburg, Va., on May 19 or 20, 1864, probably was repeated hundreds, if not thousands, of times in the town and the surrounding, war-ravaged countryside during the Civil War. Two wooden coffins lay on the ground, the bare feet of a dead soldier protruding between them while two other bodies wrapped in blankets lay nearby. A man, perhaps a chaplain holding a Bible who was preparing to give the dead men a Christian burial, gazes into the distance while a burial detail and soldiers take a break from their sad tasks. A body appears on a stretcher in the background, which also includes at least 40 wooden markers designating the graves of Union soldiers who were killed in action or died from wounds or disease in or near the town along the Rappahannock River.

(Note: This story originally appeared on Banks’ Civil War blog, which may be accessed here.) It also appeared in the CCWP’s Battlefield Photographer.

A photographer employed by Mathew Brady made this image of the burial of Federal dead in Fredericksburg, Va., probably on May 20, 1864. (Library of Congress)

In this cropped enlargement of the original above, a dead soldier’s feet protrude from behind a coffin. (Library of Congress)

Gravediggers were especially busy that spring. To keep pressure on Robert E. Lee and threaten the Rebel capital in Richmond, the Union army fought especially bloody battles at the Wilderness (May 5-7), Spotsylvania Courthouse (May 8-21) and elsewhere near Fredericksburg, causing thousands of casualties on both sides.

In his ground-breaking 1983 book, “Grant and Lee, The Virginia Campaigns 1864-1865,” Civil War photography expert William Frassanito dissected this image and six other photos of this scene in Fredericksburg. Frassanito believed the image was taken by a photographer working for Mathew Brady on May 19 or May 20, 1864, but he was unable to pinpoint its location. Years later, painstaking research by Noel G. Harrison of the National Park Service revealed the photograph was made at the edge of Fredericksburg, on Winchester Street between Amelia and Lewis streets. Using a magnifying glass to view details in the original negative at the National Archives, Frassanito was even able to identify a soldier’s name as well as his regimental number scrawled on the marker near the gravedigger’s hand at the extreme right of the photograph. Further research by Frassanito revealed that soldier was 121st New York Sergeant Lester Baum, 24, who was mortally wounded at Spotsylvania Courthouse on May 10, 1864 and died nine days later.

Thankfully, I don’t have to travel to the Library of Congress or National Archives in Washington or use a magnifying glass to closely examine glass-plate images taken during the Civil War, as Frassanito had to do while researching his book in the 1970s and ’80s. Easily enlarged, digitized versions of many images taken by Civil War photographers are available on the excellent Library of Congress web site in JPEG and TIFF formats.

In this enlargement of the original image, “SAR” and “H. Tuck” appear on the grave marker by the solder’s right foot. A shovel obscures the rest of the writing on the marker. (Library of Congress)

An extreme close-up of Sergeant Harvey Tucker’s wooden grave marker. (Library of Congress)

In another enlargement of the original image, Sergeant Lester Baum’s marker appears just below the right hand of the gravedigger at the far right. (Library of Congress)

As examination on my blog of these Antietam images by Alexander Gardner shows, the detail found in old glass-plate images is amazing, especially in TIFF format. While examining enlargements of the Fredericksburg burial image, I was eager to find details that may have been overlooked. A gravedigger’s shovel, socks on the dead men wrapped in blankets and even wording on the tall marker (perhaps Private Alexander Read of Company K of the 84th Pennsylvania) are easily seen. But it was another grave marker in the right background, next to the seated soldier, that especially attracted my attention. A shovel obscures part of the marker, but the letters “SAR” and “H. Tuck” appear by the soldier’s right foot.

Determined to identify who was buried under that marker, I spent a half-hour on the American Civil War Research Database in an effort to narrow the possibilities. I assumed the soldier’s rank was sergeant by the apparent misspelling “SAR” at the top of the marker. A reasonable assumption was that the soldier’s last name was Tucker, so I searched all soldiers with that last name and a first name that began with “H” who did not survive the war. Soldiers with last names such as Tuckett or Tucksberry were ruled out because they didn’t die in Virginia in the spring of 1864, their first names didn’t begin with “H” or they didn’t meet other criteria. Of the 13 Tuckers who did not survive the war, only one had a first name that began with “H” and served near Fredericksburg in 1864:

Sergeant Harvey Tucker of the 6th Michigan Cavalry.

Wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 6, 1864, Tucker died two weeks days later in Fredericksburg. He was 37 years old. Examination of 55 pages of documents in Tucker widow’s pension file on fold3.com revealed many more details about the Michigan man’s life — including his last days on earth.

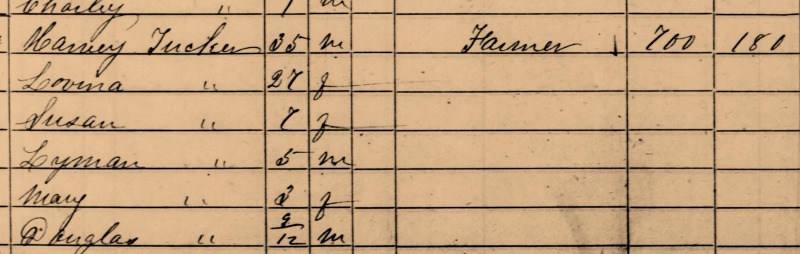

According to the 1860 U.S. census, Harvey Tucker was a married father of four children.

Thirty-five year-old Harvey Tucker enlisted in the Union army in Cottrellville, Mich., about 50 miles northeast of Detroit, on Sept. 10, 1862. Born in Massena, N.Y., he had gray eyes, dark hair, a swarthy complexion and stood 5-7, about average height for a Civil War soldier. The decision to join the army must have been difficult for Tucker, a married man who lived in Ira Township, Mich., which rises from the shores of Lake St. Clair.

In June 1860, the Federal census taker noted that Tucker’s household included his 27-year-old wife, Lovina, and four children: Susan, 7; Lyman, 5; Mary, 2; and Douglas, 9 months. (Another child, John, was born in September 1861.) A farmer and a blacksmith, Tucker had real estate that was valued at $700 and personal property worth $180, modest totals. Lovina’s first husband was abusive, and she “was taken away by her father,” although the couple apparently did not legally divorce. Born in Canada, she married Harvey on May 20, 1852, when she was 19.

Does this cropped enlargement of the original image show 6th Michigan Chaplain Stephen S.N. Greeley? In May 1864, he was 50 years old. (Library of Congress)

A little more than a month after his enlistment, Tucker was mustered into Company C of the 6th Michigan Cavalry, one of four regiments that formed the Michigan Cavalry Brigade. Its young brigadier general, George Armstrong Custer, would earn great acclaim during the last three years of the Civil War — and infamy in 1876 at Little Big Horn.

The 6th Michigan served mainly on picket duty until it saw its first major fighting during the Gettysburg campaign on June 30, 1863 at Hanover, Pa. The regiment “particularly distinguished” itself, according to General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, on July 2, 1863, at Hunterstown, Pa., where Custer set a trap and whipped Wade Hampton’s Rebel cavalry. On July 3, in a cavalry fight east of Gettysburg, the brigade fought well against Jeb Stuart’s horsemen, according to Custer, who wrote “there were many cases of personal heroism, but a list of their names would make my report too extended.”

Earlier in 1863, Tucker apparently had attracted the notice of superiors, who promoted him to corporal on New Year’s Day 1863 and to sergeant a little more than a month later. Battles in Virginia that fall at Brandy Station, Buckland Mills, Mine Run and Morton’s Ford followed for the regiment, but fighting at the Wilderness dwarfed all the others.

A regimental band played “Yankee Doodle” as the 6th Michigan Cavalry dashed into battle on May 6 at the Wilderness, mostly thick woods that offered little visibility. Armed with Spencer repeating rifles, the outnumbered Michiganders were nearly enveloped by the Rebels before they turned the tide and held the right of the brigade’s line. Sometime during the fight, Tucker was struck a little above the hip by a bullet that exited at his opposite shoulder, an indication that he may have been astride his horse when he was wounded by a Rebel firing from well below him. By 1864, the Army of the Potomac ambulance corps was well organized, and Tucker soon may have been transported 10 miles over the rough roads to Fredericksburg. So many of the town’s buildings were used to house wounded and dying men that it was often described as “one vast hospital.”

Chaplain Stephen S.N. Greeley, probably late 19th century. He died in 1892 at age 79. (Courtesy John Dickey)

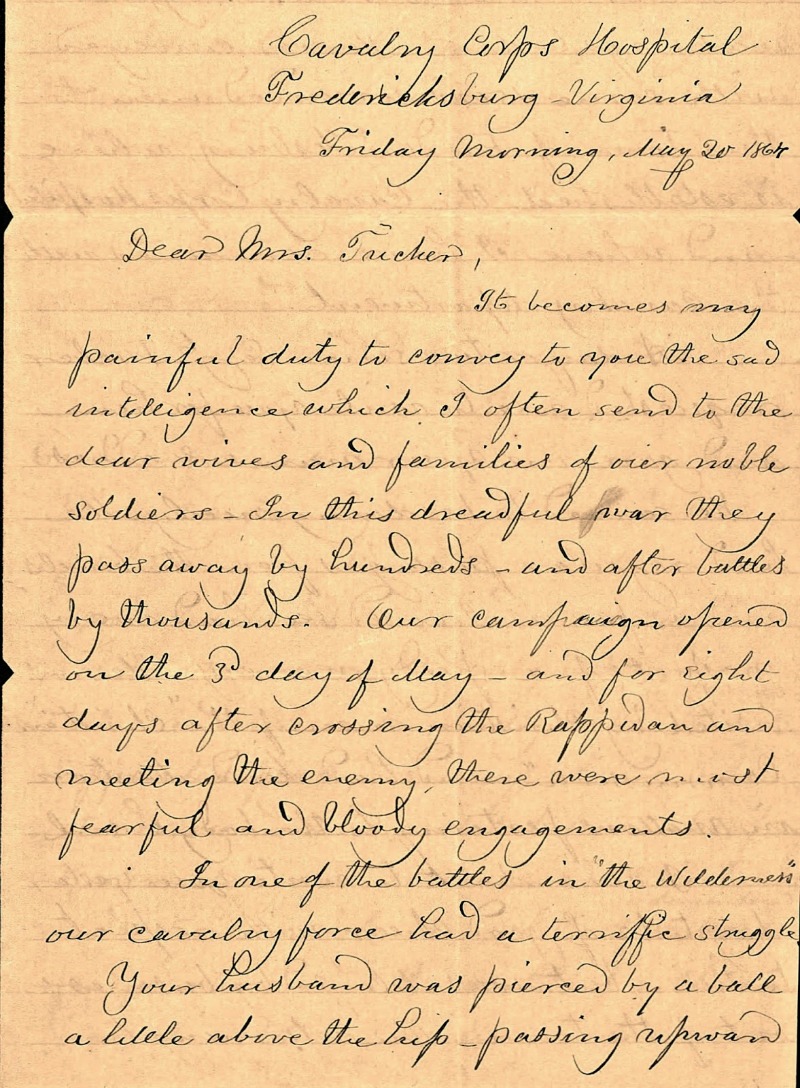

Initially, Tucker appeared to be doing well. He had “regular passages of the bowels” and gave the regimental chaplain his address so he could write a letter home to his wife. But two weeks after he was wounded, Tucker suffered an internal hemorrhage and the end came quickly at Cavalry Corps Hospital on May 20, 1864 — his 12th wedding anniversary. Later that morning, Chaplain Stephen S.N. Greeley wrote a four-page letter to Lovina Tucker to explain the circumstances of her husband’s death. (See transcript below.)

“A kind-hearted, simple-minded gentleman of the old school,” Greeley was not well suited to the rigors of war, a veteran wrote after the war. “… in the field he was more like a child than a seasoned soldier and needed the watchful care of all his friends to keep him from perishing with hunger, fatigue, and exposure.” But the chaplain, 50 years old in May 1864, toughed it out with the 6th Michigan from 1862 through the end of the war, ministering to soldiers and often breaking sad news to loved ones back home.

“It becomes my painful duty to convey to you the sad intelligence that is often sent to dear wives and families of our noble soldiers,” Greeley’s letter to Tucker’s wife began. “In this dreadful war they pass away by hundreds — and after battles by thousands.”

At one point during the war, according to Harrison’s research, Union dead in Fredericksburg were buried “four deep” and often without identification or a proper service. In a 1998 article in Military Images Magazine, Harrison wrote that a soldier detailed to Fredericksburg as part of the provost guard was appalled by the lack of concern for the dead. Corporal Albert Downs of the 57th New York persuaded superiors that the dead should have a service and a marked grave. On the morning he died, Tucker was given just such a burial.

“We had your husband enclosed in a coffin, while others were laid only in their blankets,” Greeley wrote to Tucker’s wife, ” and when his body rested in the appointed place, many soldiers who stood round and a detachment of grave diggers uncovered their heads and stood in silence while I administered for your husband the right of a Christian burial.”

Greeley’s description of the service prompts several questions:

Could the scene he described be the same scene photographed by one of Brady’s assistants in May 1864? Are the bodies wrapped in blankets in the image the same ones the chaplain described? Is Greeley actually the man holding the book in the image? There were many burials that took place at the site in 1864, so the man with the book could be someone else, perhaps a member of the U.S. Christian Commission. Further research could yield definitive answers, maybe even a photograph of Sergeant Tucker himself. Although not conclusive evidence, the date of Greeley’s letter leads me to believe the photo of the Fredericksburg burial scene was taken on May 20, 1864.

After the Civil War, workers disinterred 328 bodies that were buried in the soldier’s cemetery on Winchester Street and re-buried them in Fredericksburg National Cemetery, less than a mile away. Tucker’s body was probably originally re-buried there under a marker that read “Unknown” — one of nearly 13,000 unknown Civil War soldiers graves in the cemetery on Marye’s Heights overlooking town.

Cavalry Corps Hospital

Fredericksburg Virginia

Friday morning, May 20, 1864

Dear Mrs. Tucker

It becomes my painful duty to convey to you the sad intelligence that is often sent to dear wives and families of our noble soldiers. In this dreadful war they pass away by hundreds — and after battles by thousands. Our campaign opened on the 3rd day in May and for eight days after crossing the Rappidan and meeting the enemy there were most fearful and bloody engagements.

In one of the battles in the Wilderness our cavalry force had a terrific struggle. Your husband was pierced by a ball a little above the hip — passing upward and coming out below the opposite shoulder. This was on Friday, two weeks ago today. He was conveyed with some 15,000 wounded men to this town of Fredericksburg, where is established the Cavalry Corps Hospital — and where I have remained with the cavalry department.

A day or two since Segt. Tucker requested me to write you for him and gave me your name & address. He seemed to be doing nicely. He had regular passages from the bowels and as far as I could see had every prospect of a speedy recovery. He was visited by Christian men of the “Christian Commision” and had kind attention in matters pertaining to the body & soul.

I was about to write you yesterday to be of good cheer with respect to him, but was delayed by business of town. On returning to my surprise I found that yesterday afternoon he had been taken with internal hemorage, together with a copious discharge of pus through the wound, and died in a very few minutes. My hopes that the ball had not touched the bowels had now proved fallicious.

I attended his remains this morning to a new Soldiers’ Cemetery we have just secured. The dead were being constantly brought in from hospitals in every direction — but we had your husband enclosed in a coffin, while others were laid only in their blankets, and when his body rested in the appointed place, many soldiers who stood round and a detachment of grave diggers uncovered their heads and stood in silence while I administered for your husband the right of a Christian burial. May God comfort you in your bereavement — is the desire and prayer of .

Yours with respect and sympathy.

S.S.N. Greeley

Chaplain Sixth Mich. Cavalry

Mrs. Lovina Tucker

Bell River, Mich.

Sixth Michigan chaplain Stephen S.N. Greeley sent a four-page letter to Tucker’s wife explaining the circumstances of the sergeant’s death after he was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness. (National Archives via fold3.com,)

SOURCES:

— Harvey Tucker widow’s pension file, National Archives and Records Service, Washington via fold3.com,

— 1860 U.S. census.

— Kidd, James Harvey, Personal Recollections of a Cavalryman With Custer’s Michigan Cavalry Brigade in the Civil War, Ionia, Michigan, 1908.

— Harrison, Noel G., Military Images Magazine, “Victims and Survivors: New Perspectives on Fredericksburg’s May 1864 Photographs,” November-December 1998.

— The Union Army, A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, Volume III, Madison, Wis., 1908.